When You've Got a Job to do You Do It!

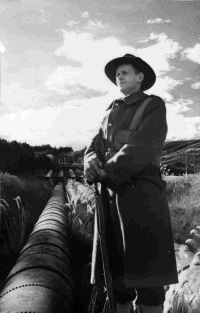

| At the outbreak of the Second World War, Lloyd Cross had already been in the army for 3 years. As an officer cadet he had been sent to Duntroon Military Academy, Australia. When war was declared Lloyd was shipped back to New Zealand and anticipated deployment overseas. The New Zealand military had other ideas and Lloyd found himself training the mass of volunteers that enlisted to fight. It would not be until 1941 that Lloyd would join up the 22nd Battalion and face Rommel in the Desert of North Africa. | |

![Behind the El Alamein front, on the eve of the successful offensive which commenced on Oct 23, a group of Maori officers study a map of the Western Desert. From left to right: Lt G Marden (Nth Ak), Lt J Aperahama (Nth Ak), Capt JC Henare (Nth Ak), Capt W Porter, [MC, Bar] (Nth Ak). Photograph taken by M D Elias. Behind the El Alamein front, on the eve of the successful offensive which commenced on Oct 23, a group of Maori officers study a map of the Western Desert. From left to right: Lt G Marden (Nth Ak), Lt J Aperahama (Nth Ak), Capt JC Henare (Nth Ak), Capt W Porter, [MC, Bar] (Nth Ak). Photograph taken by M D Elias.](https://www.kiwiveterans.co.nz/images/custom/interviews/when_youve_got_a_job_to_do_you_do_it/thmb/behind_the_el_alamein_front_officers_of_the_28th_battalion_studying_a_map_of_the_western_desert._23_octoher_1942._da06727f.jpg)                                      | Duntroon was formed in 1911 as a military academy for training officer cadets. In that first year New Zealand supplied 10 of the 41 inaugural cadets and it was a trend that would continue after the war. Duntroon offered many New Zealand officers professional military training and were the natural leaders for the conflict that erupted in 1939. These Duntroon graduates were shipped back to New Zealand when war broke out and were expecting to sail to Europe and fight, but many were appointed as training staff to shape the thousands of new volunteers into a capable fighting force. Despite the vital role of training new soldiers, many professional officers sought fighting commissions from their superior officers. For some, months of frustration followed as they felt that the training they had acquired was wasted as they were continually denied fighting positions overseas. Fortuitously, many of these valuable officers missed out on the failed campaigns of Greece and Crete but later joined the 2nd New Zealand Division in North Africa. Duntroon and Training | North Africa: Ready for Action | Italy: River after River Duntroon and Training.Patrick: Where were you born? Where did you grow up?Lloyd: I was born in Dunedin and my early life was spent on the farm at Tupeka West, Central Otago. My father got asthma down there so we bought a high country place in South Canterbury. So we moved up to South Canterbury and I went to a country primary school. There were no school buses, so you rode a horse to school, four miles there and four miles home. I went to Timaru Boys High, where my third form year I found annoying because my eldest brother was Head Prefect and my cousin was head of the house, and in those days, Prefects caned. The days I got caned when I shouldn’t of because my brother and my cousin first of all couldn’t let it be seen that they were showing favouritism. Okay, I went on through Timaru and made the first fifteen. I was an athletic champion there. Patrick: Did you have quite a keen interest in the farm as well, whilst you were in High School? Lloyd: Yes, I was keen on the farm, but my older brother left for the War so I decided that I wasn’t going back on the farm, if it was good enough for him, well …. so I went to join the Regular Army, Duntroon military College in Australia. I went through the normal time there - 1937-1938., that’s when the war clouds were gathering; we had basically run down our armed forces in NZ. There was no compulsory military training that had been abolished in 1931. And the Southland Territorials were all voluntary. Patrick: When you were at Duntroon, were you recognized as a New Zealander? Did the Aussies give you a hard time? Lloyd: Yes, Duntroon started in 1910 as a Military College; they took all the best concepts and features from Sandhurst in England, Sincere Military College in France and West Point in the United States and put them into Duntroon. They learnt all forms of the forces – cavalry, infantry, artillery, engineering, civilian subjects, languages, accountancy, mathematics, science. Patrick: So it was pretty heavy duty stuff? Lloyd: Yes. We use to call it the clink; we weren’t aloud to drink even though some of our fellas were over 21. Yet, smoking was permitted. They selected about 4 New Zealanders a year. War was declared one Sunday evening and I was on leave, I was out with some people in Canberra and I came in 10 minutes late and I was training with a bit of fuel craft so I wouldn’t be seen to put my leave pass in the box and all the lights were on and a terrific noise was going on all over the place. So I shoved my leave pass in, shot over to the village room, and through the arms they said ‘Wonderful news, war has been declared’. We were regular Army and we were training and one thing we wanted was a war, it would be great. After all, if you’re training for rugby, you going to want play a match. Patrick: So as the war clouds loomed, the School’s mood was hoping for a war? Lloyd: Chamberlain had said peace in our time and we thought that was a bit weak. So it came as a bit of a bolt out of the blue that war was declared so quickly, although we knew it was probably going to happen once they invaded Poland, which it did. We had radio verification of graduation the next day and off to war. The next morning, the commandant came in and said ‘Well gentlemen, war has been declared, work will proceed as usual, and graduation date will be the same, anti-climax’. We graduated December 12, 1939, went down to Sydney, New Zealanders were to catch the boat (no aircrafts those days) and we came back to New Zealand on the E52 boats on the Wanganella. The Duntroon Officer Cadets always travel first class and because we graduated we got 2 pips because we had been through all the probation period through the college. Patrick: So did you go through all the basic training of weaponry and all those sorts of things at the school? Lloyd: Yes, we did everything. We came back, and met the GOC, General Duigan, who led the graduates to his office, and we asked ‘When can we get to the war?’. And he said, ‘Well the war will last 30 years, they’ll be plenty time for you to get there.’ And we thought, with that sort of thinking, he’s not a very bright fella. However, we were posted and as an officer you never got posted anywhere near your home turf. I was posted in Wellington. First job I was sent to Trentham as an instructor to train these fellas coming in to go overseas. Patrick: How did you feel about that job? Lloyd: Well, we were fully trained to do it. No problem. We knew all the answers; these chaps coming in were raw recruits. They came from all walks of life, freezing workers, shearers, Sheppard’s, farm owners, lawyers, accountants, teachers, you name it. First job was training the officers and then from that, training went on to CDSI (Central District School of Instruction), training officers that were coming from the territorials Patrick: How did the army decide who was going to be trained as an officer from these recruits? Lloyd: Good question. They took officers who had been in the territorial volunteers, or who had been schoolmasters. Schoolmasters were automatically commissioned into the Army as officers in the school cadets, so they officered all the battalions in the first and second year, which included the second battalion. It was anybody’s guess to how you pick them. So you might say, this chap is a lawyer in Waipukurau, he was captain of his school rugby team, so we’ll send him to officer training. He completes a short course for 6 weeks and comes out as a Second Lieutenant. Second Lieutenant is of a probationary thing and after 12 months there, he will automatically go to 2 pips. I was in the Central Districts area, which replied to all the Northern and Southern commanders’ role. And each commander is divided into 4 areas. Central command was Taranaki and Wellington West Coast was Wanganui, Palmerston North, Levin, Wellington city and Hawkes Bay, which took in Wairarapa, Hawkes Bay and Poverty Bay. Each of those areas had commands. As men of volunteers, they’d be asked to send so many men from those areas that had potential NCOs and Officers, so they’d send down from each area, maybe 30 or 40. How they picked those was up to them. So they came down into the CDSI and we’d put them through the hoops. If they looked like athletic men and stood out, we turned them on top to be officers otherwise they’d be sergeant majors, corporals, etcetera. Patrick: In retrospect, how would you describe yourself as an officer? Were you quite hard? Did you feel that you had to be quite hard? Lloyd: Well no, I don’t think so. You can’t allow any nonsense and of course you’ve got a very strict military regimen to back you up. My first job at CDSI was training the officers and NCOs of the Maori Battalion. As I come from central Otago, I had no contact with a Maori. And about 60 of them came to me, they all looked alike, I couldn’t pronounce their names. I very quickly discovered that these Maori would have you on as far as you would go, but once you jumped on them they respected the discipline. That’s one thing they liked, they didn’t mind being ordered around. A lot of them turned out to be first class officers, one of them came in as a Private, James Henry, who finished up as Colonel of the Maori Battalion and became Sir James Henare. I got to know them very well, and have been friends with them right through life. Patrick: So coming from a background of never meeting a Maori before, and whilst being an instructor there, how would you compare a Pakeha to a Maori soldier in regards to their view of warfare? Lloyd: Well, we had two other Duntroon boys there and they had groups against my Maori group. And we had a contest, and my Maori boys outgunned them in every department. They were natural soldiers, their drill was outstanding; they had this perfect timing of arms drill (with a rifle) and presenting arms. They took to soldiering like a duck to water. They were very good on field craft. I very quickly discovered that they were tribal. For instance, the Maori Battalion was divided into 4 companies. A company: Nga Puhi, Auckland – nicknamed the gum diggers, B company: Waikato, Tainui people – known as the penny divers, C company from Ngati Porou, East Coast – known as the cowboys, D company was the less tribes from North, South, Taranaki, Wellington, Wairarapa. I found that you could not put an officer from Ngati Porou into another company than C, they hated each other’s guts. They would only respond to officers of their own tribe. Most of these officers came to us as potential NCO and were related to kaumatua. Rank counts very highly in the Maori hierarchy. So if you’re the son of a chief/kaumatua you’ve got a bit of standing on the chap who’s not. This applied right through the Maori Battalion. Patrick: Could you say that you had more fun training these guys than the Pakeha boys because their personality was pretty new to you? Having never dealt with Maori before? Lloyd: No, I had just as much enjoyment out of teaching my fellow Kiwi’s who weren’t Maori. I just happened to be there when the Maori Battalion was being formed. I felt frustrated the whole time, I wanted to get away to the war and I hated being held back to instruct. So after the third Escalon, I trained the NCOs and Officers and then I was sent as Area Officer to Wanganui, West Coast. This became my area to train. Everyday volunteers came in to apply to go to war. So we would give them a medical examination and send them off to Trentham. Patrick: So whilst training all these guys, it was a real drag for you? Lloyd: Yeah, when I graduated at Duntroon, and the war broke out in 1939, there was a total of 84 Regular Officers in the whole of New Zealand, and 300 other ranks. The Territorial was run down, there was suppose to be about 800 in strength, there was only 200. Many territorials only joined up to get a rifle to go pig hunting. The army set-up was a disintegrating hole. Patrick: Can you think of any other times of when some of the boys played up a bit? Lloyd: I remember an intake came in from the Hawkes Bay, Tolaga Bay, Gisborne, Wairoa, Hastings and Napier. They got in at 9pm on the train and many had been celebrating their last days of freedom as a civilian. Some of them were drunk as skunks. So we sent the camp man on duty down to get them in order to march them to camp. We tried to get them into 3 lines, which was hopeless. I started to get a bit toey, and one chap said ‘Who the bloody hell do you think you are anyway?’ and I said, ‘You’ll find out in the morning.’ So we woke them up at 5 a.m. in the morning and gave them the run around. Patrick: During the time that you were training, were you putting your application in to go overseas? Lloyd: Every time I saw General Duigan, I would ask him. It was In July/August 1941 when I got the message. Went on the Aquitania to the Middle East and straight to the twenty-second. At this stage they had fought through Greece and Crete. I was in the Wellington 9th platoon. Great fellows. Patrick: Were they all veterans from the Crete campaign? Lloyd: No, about 50 – 50. The first 3 escalons, then the 4th reinforcements, the 5th , 6th and the 7th, then there was one big gap between those and the 8th because the 3rd Division was formed and sent to the Pacific so we were getting no reinforcements at all in the Middle East. Once Singapore fell we were getting surface mail, 3 to 4 months old, there were no reinforcements. Patrick: Was mail essential for morale? Lloyd: Yes, some men were married with children, others were engaged and wanted to know whether they were still engaged. North Africa.Patrick: What was your first impression of Egypt when you got there?Lloyd: Once we arrived at the Southern end of Suez Canal the smell was the first thing that hit me. It was a mixture of bad hygiene, marijuana and bad sewage. There were millions of people and people trying to sell us rubbish items and bad food. Patrick: I take it you would have been pretty excited once you got to Egypt, waiting all that time and being frustrated being stuck in New Zealand training. Were you quite ready for action? Lloyd: Yes, I was very ready for action. I took over 9th platoon in A company. I very quickly realized that the standard you were trained in at Duntroon is not the standard you can expect in ordinary discipline and routine with a bunch of volunteers. I also had to learn from the fellas that had been through Crete that they knew their stuff. I listened to them. It was a team thing – whatever you were – you slept together, ate together, died together. We had a rule in our platoon. Officers go last at meal times, if there was not enough food, officers would go without. When you are out, there is Officers mess; otherwise you eat with your company or platoon. Patrick: Did you find that your company and platoon proved to be quite a good team? Lloyd: Yes, much more informal because we lived, fought and died together. An officer is rarely called ‘Sir’ he is called ‘Boss’. Patrick: Are you able to describe for me the first time you experienced action with the Germans/Italians? Lloyd: We were sent down to Mersa Matruh to block a port. The Germans didn’t realize we had cut the road. Platoons were on each side of the road and 8 German vehicles came and we shot at them, killing the German’s in the vehicles. Another time, 3 of our tanks came down. Two were being used by Germans and opened fire. Our shells bounced off these tanks. We took out the 2 tanks with a couple of two pounders. Our other method of taking out tanks was by sticky bombs – you pull a pin, and stuck in on the tank and in 4 seconds the tank would blow up. They proved to be useless, as it was hard to get close to the tank. We buried all the bombs. We had no defense against tanks. One morning we lost over 400 from Battalion because we had no tank support. Patrick: Did these 3 tanks inflict any casualties on your Platoon? Lloyd: No, fortunately, it was a short battle that lasted 15 minutes. Patrick: How did you feel being away at military school and then getting a rush when first going into the line of fire? Did you get excited? Did you get afraid? Lloyd: I got an adrenalin rush yes, not a fright though. Some situations are worse than others, some situations I found my mouth went dry. You get thirsty as hell, but you’ve got a job to do and you do it. Patrick: In the early stages of the desert campaign we seemed to suffer defeat after defeat under Rommel. Why do you think this happened? Can you remember any actions that suffered from incompetent leadership or Strategy? Lloyd: We weren’t attacking as a division; we were being split up and moved here and there. Rommel had a couple of armoured divisions with him. He might come up against a Brigade or less, easy pickings for him. And that was why he was so successful because he was mobile and hard hitting and he hit with a powerful force against weak opposition. One such disaster happened during the 2nd Libyan Campaign: This time we went in o.k. and suddenly we were being shelled; we stopped and hit the deck. These shells were getting in amongst us but it was one of our Allies shelling us, the 4th Indian Division. The Germans must have been observing us with some interest. We had a troop of 25 Pounders from our 5th Field Regiment and they dropped their trailers and returned fire. This woke the Indians up because they recognised the sound of the 25 pounders. Then Germans from Bardia then got into us. So we got back in the truck and went like hell, we had a few casualties. We reached Fort Capuzzo and met up with 28th Maori Battalion and 23rd South Island Battalion. Then our Colonel (Colonel Andrews, 22 Battalion) took over the Brigade and our 2IC (Second in Command) took over the Battalion. We were there for a while and we seemed to get shelled every meal time from Hellfire Pass. Then one day a German armoured car came racing past and machine gunned our position. My Boyes Anti Tank Riflemen was a terrific shot but at that particular time he had it in pieces cleaning it and oiling it (The Boyes Anti Tank Rife fired a one inch shell and had a hell of a kick to it). And by the time he reassembled the flipping thing the Germans had taken off. It was completely ineffective against German Armour. So we started marching for a while that night. We never knew where we were going – communication was very poor. We went past Tobruk; we still had no idea where we were going. Our Company Commander ordered us to bed down for the night and we kicked out at about 5 in the mourning and this was the middle of winter. It was as cold as hell out there, we had battledress on, leather jackets on, we long woollen underpants on – it was cold. Our Company Commander said “We are going to Gazala” which was just a place on a map “And if the Enemy are there will attack and destroy them and have breakfast. If it’s not occupied we will occupy it and have breakfast” We reached Gazala and bullets started hitting the truck, so we jumped out of the truck and hit the deck. Me and another Platoon Commander went over to see the Company Commander who by this stage had grabbed his Sergent Majors bayonet and was digger a hole like a rabbit, scratching for dear life and he was yelling “Get Down! Get Down! You’ll get killed!” So we said “Argh, forget him” and left him to it. We took our two Platoons forward and could see the other Company’s had spread out and started moving forward so we spread out, fell in line and went forward with them until we came to a plateau that dipped down into a big hollow. We could see the other two Company’s had gone to ground so we went to ground. In front we counted 16 enemy field guns; we were looking right at them. We were in a slight depression, so the enemy shells dropped too short and hit the ground in front of us, and if they lifted a bit, it went up behind us. Anyway, we got no breakfast…. and we got no Lunch…. and we got no DINNER!!! (Ha-Ha). I sent blokes back in all sorts of different directions, as did the other Platoon, looking for our bloody Company Commander. He had kept the other Platoon commanded by a Corporal. Anyway, we were getting pretty hungry! It was so cold that night we couldn’t sleep so we dug to make trenches and strengthen our positions. The next morning, we managed to contact our 2IC and he been were wondering where were and our Company Commander hadn’t seen us! He had no intention of looking for us; he was 500 yards behind us. So after 3 days a bit of paper came through informing us to proceed over there [to the right in flanking manoeuvre] and attack this strong point. Artillery would open up at 0630 hours, Vickers would open from the left and Mortars would open up just before we went in. The other Platoon Commander said “I’ll tell him to go to hell with those sort of orders” because he knew what was over that ridge. Well I thought, I’ve got the orders so I’d better go. Off we went and the due time came, at this time it was getting a little bit light and there was no sign of any shelling. Suddenly, whoosh, whoosh, whoosh. Our Artillery fired 4 shells, 1 per gun and that was it. Our Mortars opened up and they were landing behind us. I thought, to hell with this! I was at a loose as to what the hell is going on. I was determined to have a go at this so I said to the blokes “Right Platoon we gotta go” … “Forward!” So we got up and we charged. I counted 8 separate machine guns that had us in their enfilade of fire. After about 100 yards I yelled “DOWN!” We had three goes at this and each time we came under a hail of withering fire. We had 600 yards of open desert with no cover what so ever. They had us cold. And I thought “if I go any further, I’m going to lose the whole Platoon”. I had to make a tactical withdraw. I had three sections I had to leap frog back. So two sections fired, and the other section retires. So it was this continuous firing that kept the Huns head down. Nobody died and only 2 were wounded. Thank God for that! I felt very disappointed. I found out later the Mortars had opened up and they found their range was too short to hit the enemy, there was no liaison, this should have been done the day before, they should have zeroed in the day before. When the Vickers opened up they discovered that we were right in the line of fire, so they ceased firing and the Artillery only gave us four shells! Patrick: Was this a common occurrence? Lloyd: Well things usually go wrong, but it should have not gone as wrong as that. It was incompetence of the company commander who didn’t have it – it was gutless. My sergeant went to Colonel Andrew and said “Get rid of our company commander or we will.” Colonel Andrew was aware of his incompetence and said “I’m waiting for a chance to dump him”. So he was basically sent home. Patrick: Would they have told him why they were sending him home? Lloyd: He had never been near our platoon. That area I attacked with that platoon, well the following day, the Poles attacked it and got shot to pieces. We would have been obliterated if we had carried on. We had no Armour! Patrick: What was the most intense piece of conflict whilst in the desert, the heaviest encounter with the Germans? Lloyd: El Alamein. I missed the Ruweisat Ridge debacle as I was bit by a mosquito. Patrick: What was your role in the Battle of Alamein? Lloyd: They re-formed D company (Taranaki) and I went over there. We went in the attack and I took over the company. We reached the objective on time with a few casualties. It was very heavy fighting as it was our first real proper night attack. However, you were certain that tanks would be there in the morning to support you in a disaster. Freyberg demanded we have a tank brigade under his command so the 9th British Armour Brigade was posted to the New Zealand division. They were very happy to be part of the New Zealand division and painted a fern leaf on their tanks. Patrick: What can you tell me about the preparations before the battle of El Alamein? Lloyd: Before the battle of Alamein it was our first set piece night attack so in our company we prepared for attacks at night. We assimilated 10 commander causalities with sergeants taking over, and assimilated sergeant casualties with corporals taking over and so on. So we had chaps who could take over and do the job above them. Everything was perfect provided you did your time correctly. The artillery would open up and would fire what was called a Creeping Barrage. The idea behind a Creeping Barrage was to be right behind the bursting shells. With the 25 pounders with a shell howitzer, when they exploded all the shrapnel would go forward, they had very little back lash. You could follow behind at around 40 yards. So we would follow tightly behind the barrage and deal with Hun before they got their heads up. We also had a live practice so we knew exactly what to do. Patrick: How did guys react to that? Lloyd: Pleased. At last we might be able to get our teeth in without a disaster. It was Montgomery’s first performance. We meet him one day in the Alamein box. A jeep came towards our platoon, Freyburg was in it and there was this funny little bloke who had his shorts down to his knees, his socks up to his knees, he wore an Australian hat with a New Zealand hat badge and the grey Marino sheep’s wool jersey that was unique to the New Zealanders. Anyway, he came up to my Sergent and asked “Where did you win your DCM?” And he said, “Ruweisat Ridge” and he then asks, “What do you do in civilian life?” “I’m a Farmer Sir.” ””…And where’s your farm?” “Taihape Sir.” ”…And where’s Taihape?” ”Well, you know, King Country” “…And where’s the King Country?” “You know? Up the main Trunk” Montgomery gave up and walked away and my Sergent turns to me and says “What’s wrong with that stupid basted, he doesn’t know where Taihape is?” So that was my first encounter with Montgomery. He was a showman who knew how to get publicity. And he tried to stop our rum ration! That was dreadful but he didn’t get away with it. Patrick: What was the reason behind the rum issue? Lloyd: It warms the inside of the system. One fellow had never ever had a drink in his life, he took his first double Russian and got drunk. Some people say it gave you courage. It is very strong alcohol as they take pre rum (100% alcohol) and broke it down to 1 in 10. One issue was an ounce per man. The rum we had was very strong. One fellow had never ever had a drink in his life, he took his first double ration and he got very drunk. And he went round and round in a circle, he couldn’t stand up properly. He must have travelled the distance between the start line and the objective probably twice over before he even got to the start line. And he went out with “physical exhaustion”, I’m not kidding. Patrick: When it came to the hour before an attack, what were your feelings and emotions at that time? Lloyd: You were so busy as you had a job to do. Checking everything so there is no hiccups along the way. My mouth was getting dry and my stomach was churning. It was the waiting that was the worst thing. Patrick: What was the sequence of events for you during the Battle of Alamein once you got the green light to move out? Lloyd: Firstly, it was absolute din with the artillery barrage. Every gun in the 8th Army opened up. There was the 8th and 9th Australian division, 2nd New Zealand division, 1st, 2nd South Africa division, 4th Indian and 51st Highland division. The New Zealand division was the only division that reached its objective on the first night. Aussies had a hell of a fight up the top end. The Aussies secured their objective the following night, then the 51st Highland, then the South African division. Before the barrage lifted we did 100 yards every 6 minutes. So the 21st Battalion did the first 100 yards, 22nd and 21st passed through them and carried on to our objective to Miteiriya Ridge. The 23rd didn’t think they would reach their part but it did. They went past us, and actually copped the barrage twice and had a few casualties. In reserve was the 28th Maori Battalion and they went in. The biggest impression was the noise of the barrage. You had to shout your head off. With heavy dew, the smoke from the bursting shells, it created smog. The smell of a corpse will never leave your nostrils. Those movies like ‘Saving Private Ryan’ can never get that one element. Patrick: In the first night of the Battle of Alamein, how many yards did you gain? Lloyd: 500 yards Patrick: Throughout the whole Battle, what was the most terrifying moment for you? Lloyd: When we got to the objective. Patrick: How would you describe the opposition that you came across once you got to the objective? Lloyd: The Germans always had defense in depth. You never had a true frontline. They’d have a strong point, another one there, and another one there. Three yards further back would be more strong points. You might clean the front line and think that’s it, but no, you’ve got more and more. The German’s one weakness was all their machine guns used to throw about 1 in 10 tracers which told you exactly where they were. So we would wheel half a section behind them and shoot them down. They never woke up to that, right through the war. Patrick: Did you ever have to resort to hand-to-hand combat when you came into those machine gun nests? Lloyd: Yes, you’d shoot them at about 5 yard because the Germans hadn’t put their hands up. You hit first, or you may not get another chance. Patrick: What do you remember the most about the times when you were in action. Lloyd: All the luck. Patrick: Are you able to describe to me when you were lucky? Lloyd: Yes, I got blown up. Just before Alamein where the Germans made their last push on the South of the Alamein box. Engineers were setting up a minefield and we were sent up to provide covering fire for them while they were laying it. The next morning we were told to dig in and fight by Brigadier Kippenberger. We lost 1 whole section because the German tanks came in with Infantry behind them. I thought “this is it”. Our artillery opened up and got into range and the Boston Bombers came over and got stuck in. The attack was halted. So we were saved. That night, we were told to pull out otherwise the Germans would just run over the top of us. Our truck was bogged down in the sand, so we got it out and went on until we struck the wire, which was in front of a minefield. It was very dark with a bit of fog. I said “Halt, there’s a wire”. The driver accelerated and we hit the wire and all I remember was a flash and wakeing up in heaven. I heard birds singing and thought, “this is great I made it to heaven”. I felt my legs and than came to and all I saw was stars. The driver was killed. All the front of the truck was gone. I had my platoon on the back of the truck and a few were injured. So we went back to where we were supposed to be. The next morning Colonel Russell came to the jeep and thanked me for what we had done the day before and shouted me a whiskey and away he went. An hour later, he was killed at the same minefield that I was blown up at the night before. He went to assist a British vehicle in the minefield, trod on a mine and was blown to pieces. Patrick: How would you describe the rest of the battle of Alamein from your perspective? Lloyd: At night, we were pretty busy, peering through the gloom. Waiting for a machine gun to burst, hoping you didn’t stand on a nest mine, which has 3 prongs that stick up out of the ground. If you tread on it, it explodes about 3 feet above the ground. They’re full of ball bearings – if you’re within 15 yards of it, you’ll get clobbered. Patrick: Did you witness one of them going off? Lloyd: Yes, fortunately I wasn’t the recipient. An officer got shot in the buttocks by a ball bearing but he survived. However, in Italy he stood on another one and died. We saved a lot of fellas with morphine. I carried 6 phials of morphine. I would give them a shot of morphine. But quite often it was the shock that would kill you, not so much the wound. Patrick: How would you describe the battle scene after the first night? Lloyd: Dawn came; we were ready for a counter-attack. Fortunately tanks came. They had to come up, but on the way our fighter-bombers clobbered them. So the next day, Colonel Tom Campbell – told me to take my company and to pass out through the Maori Battalion and go out to protect the engineers who were going to put a mine-field in front of us. So we went out, the engineers started putting their mines in and noticed that the Germans were also laying a mine-field in front of them. Mines were put all over Egypt. Patrick: Was it worth putting all these mine fields down? Lloyd: Yes, it was a defensive screen. I was protecting our engineers and the Germans were protected by tanks. We could hear them crawling, the old tracks rounding up. I could see these Germans putting mines in. We did not fire because our engineers would get fired at. So, time got on and I went to the Command engineer, Major Skinner, and told him that we were not going to be here in daylight and asked if he wanted a hand. They didn’t need a hand so we went out, went through the Maori Battalion and then machine guns started running. They had forgotten about us. Patrick: Was the battle of Alamein the heaviest fighting you encountered during the war? Lloyd: No. Patrick: How did it compare to the Battle of Casino? Lloyd: Cassino was the dirtiest campaign I was ever in. It was wet, cold and terrible. Patrick: The battle of Alamein lasted two weeks, how much of that time did you spend on the front lines? Lloyd: We basically did a cover scene, then pulled out the following day and were relieved. We held back and got ready for a break through. The barrage is called the attack, the dogfight is what goes on for the next couple of days, the breakout is when you smash through and you’re away. So they pulled us out. The Italians were coming in their thousands. The Germans were retreating. So in the breakout, we were flat out, we were in a place called Dama and we were able to outflank the 5th Brigade. We were going to cut them off, and then it poured with rain. So we couldn’t move and the Germans got away. Patrick: Can you describe the aftermath of the battle? Blown up tanks? The dead? Lloyd: Yes, the dead were picked up eventually. A War Grave Commission was where they were to be buried. We stuck a rifle in the ground and a tin hat on the rifle. That was their grave. I had a Maori Battalion man one time and we had some dead enemy. I told him to bury these 3 people. He dug down about a foot deep. The smell of a dead human body is far worse than the smell of any dead animal. We could still smell the bodies and he then got some Italian perfume from one of their wrecked trucks and poured it on them to get rid of the smell. Patrick: What was the most terrifying experience for you in the desert campaign? Lloyd: I suppose going to heaven. Italy.Patrick: What was your role during the battle of Cassino?Lloyd: We were in the Armoured Brigade and I was commanding Support Company, which were machine guns, mortars and anti-tank carriers. The 22nd never attacked Casino, we went and occupied and held it. Cassino was pulverized to rubble. It stunk because none of the dead were buried. When the fine weather came, we could cross the Rapido River. The tanks couldn’t operate because of the weather and the bombing of the town, so it became a stalemate until the weather came right. We put on attacks when the weather went good. Patrick: Can you describe the heaviest fighting you experianced in Italy? Lloyd: Italy was a continuous attack. River after river after river. There were stock banks on the top of each river. All the way through, attack after attack. It was heavier than in Egypt. Patrick: How would you compare the Germans you faced in Italy to the German soldiers you fought in the desert? Lloyd: They were a different type of German. Desert Germans were confident in their ability and well lead. The enemy in Italy seemed to be more fanatical and the Nazis were not nice fellows. Patrick: Did you find that their tactics changed dramatically? Lloyd: The first 12 months in Italy, the Germans were tough. The last 6 months, they fought hard but I think they knew that they had lost the war. Some surrendered more quickly then they would of 12 months before. Patrick: Can you please tell me time when you took the surrender of Vice Admiral Rigele ? Lloyd: When we got to Trieste, we got into the square. The Colonel told me to go up and capture San Guisto Castle. On the way up there was firing at all directions, it was a shambles. Germans wouldn’t surrender to Yugoslavians, as they didn’t recognize them as an Army. We went to the castle, borrowed an armoured car and made contact with the German commander. He said that he would lower down the bridge. I got my company and a troop of tanks and we went out to the courtyard. The drawbridge dropped. We went in and the Yugoslavians were shooting the German wounded. So we had a full surrender. They laid their weapons down. I haven’t got the luger, I sold that to an Amercian - they always wanted to get one so there was a good market there. He had a good German name: Vice Admiral Hermann Rigele. I’ve got his hat and jacket. We were talking and he said it was the second time in his life that he had had to surrender. He gave me his watch, car and radio. He’d been to New Zealand about 4-5 times. He was in the German Navy. He liked New Zealand very much. He would never surrender to the US, but quite happy to surrender to an organized Army, which we were. He was a hell of a nice bloke. So anyway, night got on and we couldn’t get any food, so we asked the Germans and they fed my company. Patrick: Did your boys get along with the German soldiers? Lloyd: Yeah well they fed them. My sergeant came to me and said “Some of the Germans are getting very drunk”. So I told the Admiral who shouted orders and the trouble finished. I was impressed with the Germans discipline, even under surrender. So I dined with the German officers and we had a discussion, it was asked, “why did you (the Germans) start the war?” They replied, “we didn’t start the war – you did”. Technically, they were correct as they invaded Poland and England declared war on Germany. It was pure semantics. Patrick: What was the most terrifying moment for you in Italy? Lloyd: There were lots of moments. The worst moment was in Casa Elto on 14 December 1944. It was a night attack and I took my reserve platoon in and we got caught in a shoe minefield. The mines were about the size of a brick and blew your legs or feet off. On my right I had Sergeant Fowke and he trod on one and died, and on my left I had a chap who also trod on one who died. As he went he said “Fuckin bar…” and he was dead. I thought, every time someone moved, someone died. Above us, there was machine guns going and I could hear the Germans whispering. It was snowing and visibility wasn’t great. There was a drain that we crawled through, we reassembled and came in the rear and cleaned them out through the rear. On this mine field we felt hopeless. You’d do a night attack and if things went well, you’ll get 1 to 4 casualties. So if you went in with 120 men and 30 men wouldn’t turn up for breakfast that was an ordinary night. Most would be wounded. 25% dead and 35% wounded. Patrick: Did you suffer any wounds? Lloyd: Scratches, but never went out wounded. I was deaf for a week, had headaches for another week but we just carried on. Patrick: Can you think of any other tough situations you involved in? Like being stuck in that mine field? You had a few run ins with mines. Lloyd: Yeah (ha ha). I remember a funny story. Every night we had attacks on and this one chap would disappear but he’d always finish up at the cookhouse. We couldn’t pin desertion on him because that was very hard to prove. He’d say he got lost at night-time. We told him, if he attempted to run, we’d shoot him. Anyway, he got wounded one night in the leg and became a casualty. So the stretcher fellows put him on the stretcher and then 2 Germans came along. The stretcher fellows pointed to their Red Cross badges, but the Germans started shooting. So the stretcher fellows dropped the stretcher and started running. All of a sudden the wounded chap went running past them. So much for his wound. Patrick: How would you describe the Kiwi soldier that you served with? Lloyd: In the main, we had volunteers, they were different, very disciplined - more so than the Aussies. They had initiative. New Zealanders had much pride of themselves. Aussies would walk around like the owned the place; Kiwi’s would walk around and wouldn’t give a buggar who owned it. |