At A Distance It Was Just A Casualty

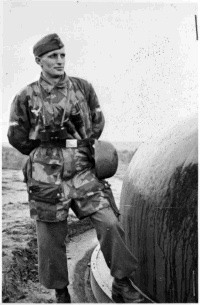

| As a Corporal of C Company, 22 Battalion, Ken F left New Zealand with the Second echelon on 2 May 1940. As the plans of Operation Sea lion were decoded, the Second Echelon was diverted from the Red Sea to bolster Great Britains Defences. After the ill-fated defence of Greece, Ken’s third encounter with German forces would bring his first real taste of combat. Through the flames and the fury brought fourth by the German Luftwaffe, Ken was forced to face the cruel realities of warfare. | |

| The key to holding Crete was the defence of the strategically important airfields at Maleme, Retino and Heraklion. Maleme was to be the responsibility of the 22 battalion, with support from the 23 and 21 battalions. Initial German moves proved to be disastrous as the defenders picked off descending airborne units who also struggled to gather their heavy equipment or seriously threaten the Kiwi positions on and around Maleme. Due to poor communication, error of judgement and the isolation of units and commanders, those responsible for command decisions miss-read the situation and withdrew from the vital airfield of Maleme. The Germans were now able to bring in much-needed supplies and reinforcement through Maleme and swiftly take the island. Criticism has been placed at Freyberg for the loss of Crete but poor communications and disunity of command played a major role in the losing of a strategic position that should have stayed in Allied hands. Ken: He wasn’t looking towards where I was, he was looking towards this Bofors Pit, thinking there might be someone there. I had a clear shot. I don’t know what the injury was, but he had sufficient consciousness to get back and sit back up against a little bank, and it was when I was going to see what happened to the other half of my platoon that I happened to pass him. When I came back, that’s when I had a look in his pay book and saw this photo of his, I presume, his wife and his two little kids. That’s when I realised of course the stupidity or the futility of it. Patrick: How did you feel when you opened up his pay book, what did you see? Ken: You know, I thought, there’s a woman smiling away, little realising that she’s a widow because that photo must have been taken some time before. But I knew she was a widow and I knew these two boys, were orphans. And that’s when I realised, you know, here’s this poor guy who’s fighting the war for an ideology that’s forced him to war, here I am going there as a volunteer to fight the war as some kind of adventure, two different people altogether really. Isn’t it? You know, I stopped to think, why I stopped to think I don’t know, these thoughts flashed through my mind, that told me that I made this woman a widow and subsequently I started to think, I wonder what help she’d get in post-war life, and what help her children would get and whether they would have any bitterness if they met me, to think that I’d killed their father. In later life, we became honorary members of the German Paratroopers Veterans. Because after the war in Germany, General Student who was in charge of the paratroopers, was charged with violations of ill-treatment to British soldiers, in particular, and one of the guys on the Nuremberg trials was a Major General Inglis and he said "No, there was no problem at all", that the Germans treated the prisoners of war honourably and all the rest of it. And as a result of that, General Student, who was head of the Paratroopers. And their association of course, made us honorary members of the Paratroopers Returned Veterans Association. So you know, that showed the attitude between two people, Inglis a NZ soldier and Student, a German soldier. As far as I was concerned, it was a sort of a fair fight, you can put it that way. Patrick: Was this your most poignant memory of your service? Ken: Yes, really. Because you didn’t very often get to a point that you were dealing with the individual. Even 200 yards away it would only be a person. But it became an individual when I shot him and then subsequently went through his gear. 200 yards away, it was a casualty. From a distance, you could have shot someone and you wouldn’t know if he was wounded or killed because you were just far enough away not to be involved. It’s not very often that you would get that situation, that you were close enough to see the person you may have shot. |