Barb-Wire Happy

| On the 12 of Sep 1941 Orm Poppleton left New Zealand as part of the 7th Reinforcements. On reaching Egypt, Orm was detailed to 22 Battalion, 5th Brigade, 2NZEF. After escaping capture at Minqar Qaim, Regimetal Number: 47879 was taken Prisoner by the Germans at Ruweisat Ridge on the 17 of July 1942. For the next 35 months Orm would move from camps through out the Riech. Determined to keep into trouble, escape was always on the mind. The first leading him to Titos men, the last time to Freedom. | |

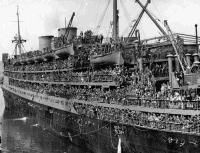

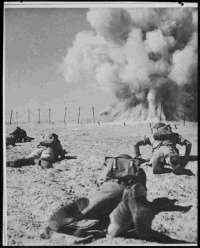

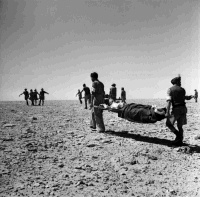

![support planes patrol New Zealand columns as they leave Mersa Matruh [Egupt], bound for Minqar Qaim [Egypt], where they first contacted the enemy. Only once, at the beginning of this campaign, was transport bombed. support planes patrol New Zealand columns as they leave Mersa Matruh [Egupt], bound for Minqar Qaim [Egypt], where they first contacted the enemy. Only once, at the beginning of this campaign, was transport bombed.](https://www.kiwiveterans.co.nz/images/custom/interviews/barb-wire_happy/thmb/low_flying_figher_support_patroling_nz_columns_in_egypt._photograph_taken_by_h_paton_ca_9_july_1942._da06890.jpg)                              | Rommels Afrika Korps captured 4342 Kiwis in the North African campaign making this theatre the most costly for the 2nd New Zealand Division in POW’s. The Western Desert was the scene of such actions as Minqar Qaim (June 1942) where the surrounded Division broke out, losing 1000. There were other costly engagements that year such as the failed attempt to capture and hold Ruweisat Ridge where over 1400 men were killed, wounded or captured and the El Mrier Depression where the 2NZDiv lost 900 to the German 21st Panzer Division in July. By the end of that year the 2NZDiv was in poor shape. It had lost 4600 men with 822 killed in action and many were sent off to prisoner of war camps in Italy. One tragic episode occurred when 160 Kiwi POW’s were killed when two ships carrying prisoners were hit by allied torpedos fired from submarines in the Mediterranean. The life of a prisoner of war was a mixture of frustration, depression, anger, hopelessness and uncertainty. Of course many sought to escape at the first opportunity and 716 succeeded in gaining their freedom. In escaping into occupied territory, the local population aided many escapees and some even joined resistance movements, witnessing first-hand the upheaval and privation that the war brought to civilian populations. Some POW’s made it safely to Spain, Switzerland, Southern Italy and Turkey. War is Declared:Orm: I was born on the 12th of May 1915 in Wellington where I grew up. When I was 17, I joined the Wellington fire brigade. I had served there right up to the outbreak of war. In 1940, I got legal absence from the fire brigade, joined the army and was sent to the military camp at Waiouru which they were building. It was just a new camp, and it was my job to set up the fire service there. Once I got that settled I spent 12 months up there before I was sent to Trenthem to prepare to go overseas.Patrick: What were your initial thoughts when you first heard that War was declared? Orm: Not good. But I thought well, it was up to all able men to step up and do their duty for their country. Patrick: What were the conditions like at Waiouru Camp? That’s New Zealands main Military Camp. Was it difficult to set up the Fire Service there? Orm: Well, it took quite a while because there were no buildings there, only tents. Waiouru is a very rugged place. It’s a good place to have a training ground (chuckle). There was no fire station so I had to start from scratch. I had to build an actual fire station; I had to put in a fire alarm system, and to train the men. I had to get staff from various places. They were hard to find because they all had jobs up there but eventually I found 5 Maori boys that worked on the dust cart in the day time and they knocked off work at 3 o’clock. I asked them if they were prepared to work for me after they knocked off. I achieved all this in less than 6 months and I put in a further 6 months and then applied to go overseas. When I decided to go overseas I had to get a relief (replacement) to take over the fire station. Then I went to Trenthem military camp for 3 months training before overseas service. To put it basically, the training was all about discipline. Patrick: Did you feel that the training was adequate in preparing you for overseas service? Orm: Oh yes, I’d never had a rifle in my hands before joining the army so they had to train us in how to use various weapons. We had good instructors. Patrick: What sort of feelings and moods did you have in the initial stages of the training, - were you rearing to go or a bit apprehensive? Orm: No, no. Like everyone else we went there and did what we were told and hoped that we could contribute to the war effort as best we could. Patrick: Can you think of any funny or memorable parts of your training or maybe some of the mischief that you and your mates got up to? Orm: No, I don’t think so, because everyone was so serious and everyone was absorbing the discipline that they were trying to instil in us. We just went along with it. Patrick: How well did you feel you were informed as far as what was going on overseas? Did you feel you had a pretty good idea of what was happening? Orm: Ohh, yeah. Patrick: What was the main way of you finding out what was going on? Orm: The radio, or “wireless” and news media. Patrick: Can you please describe how you saw the old news reels? – Was it like going to see the movies today? Orm: True, that’s right. The National news I think they called it. We used to get reports from the BBC at 9 o’clock every night from the overseas news about what was going on and the different war fronts. Patrick: Did you feel that the British were confident about beating Hitler as you were gearing up to join them? Orm: I don’t think they ever gave up their confidence. Patrick: What were the last few days like for you prior to leaving New Zealand? Orm: For myself, very stressful and probably more so for our families. I wasn’t married before I went away, I was engaged to be married but said I wouldn’t get married until I got back. That was four years later. Patrick: Did you harbour any fear at that point? Orm: I think you had fear all the time, some show it and some don’t. Patrick: Can you remember the date you shipped out on? Orm: September 2nd 1941. – The Joanne van Hander belt (chuckle). She was a Dutch luxury liner. Patrick: What was the send off like as you were leaving, - the general atmosphere? Orm: Oh well only relations were allowed on the wharf and that was it. We were on the boat for three days before we sailed. We couldn’t sail until the naval escorts were ready. Patrick: Was it a very emotional send off? Orm: Yes, yes it was. Patrick: What were your thoughts at that point? Orm: Well I didn’t know whether I was going to come back or not. I wasn’t sure if I was going to see New Zealand again. Patrick: What was your first destination? Orm: Just off Sydney. We didn’t land there, we picked up another convey at Sydney and the first stop we made was Fremantle, and we got leave there then we went from Freementle to Ceylon, we got leave there, and from there to Egypt. The Western Desert:Patrick: What were your first impressions of Egypt?Orm: Not very good, (chuckle). But it wasn’t long before we went into the first camp. That was Mardi and once we got housed in Mardi there was plenty of Sergeant Majors there to knock us into shape and we knew which way we had to go! –Where we were told! Patrick: What did you think of Maadi camp? Orm: She was a good camp. Patrick: Did you have much to do with the other camps around? Orm: No others camps, when we first got over there. We had to do a lot of guard duty at hospitals and different places. That was just to soften us up and get us ready for fighting. Then we went down on the Canal, and we trained for assault landing with the Navy. We eventually had manoeuvres down the Red sea and had a mock landing on the Sinai desert. We were trained for that but it was never used. Patrick: How much warning did you get before you were sent into combat? Orm: We went up the desert to the front lines 2 or 3 times. Then we went from there over to Syria, Palestine and Lebanon on guard duty and we were right up at the Turkish border. Our battalion was doing guard duty around bridges, and tunnels, and different spots where they thought there might be trouble. We were up there for three or four months. Then things got a bit bad in the desert so they brought us back into the front line again to stop the advancing Germans Patrick: Are you able to describe some of the battles you were involved in? Orm: Well the first one was Minquar Qaim. We were guarding some place and ohhh, we saw the German convoys coming down, and all day they were going past and they encircled us. We knew that we were in trouble. Not only were they circling us they were dropping bombs, their air force, and the orders came round that we were going to make a break at midnight with the Maori battalion leading the way and we had to get out the best way we could, with whatever transport was going out we just had to use that and luckily there was the artillery that had transport as we had none, it was gone. A lot of us got out, but we lost a lot of men. Patrick: Did the Stukas put a bit of fear in you? Orm: Yeah, they used to dive at us out of the sun, couldn’t see them, you could only hear them. Very accurate, yeah. They did a lot of damage. Patrick: Was it quite a close quarter, heavy battle? Orm: It was a very heavy battle. I got wounded there, and my mate put me on the barrel of a gun, a 25 pounder. He held me there and we got out that way. We were lucky. Patrick: Where were you wounded? Orm: Well I got a bullet through me leg. Patrick: How did it feel? Orm: Getting hit? Well you just stiffen up and wonder what the devil has struck you! Luckily mine just went straight through. It stiffened my leg up and I couldn’t walk. But I was fortunate and it healed up. I was alright. Patrick: With that being your fist encounter with battle, what were your initial thoughts? Orm: Well that’s what they train you for. You’ve got to discipline yourself. Keep calm, or try to keep calm. Keep as calm as you can. (Ha, Ha) Patrick: What were your first impressions of the German army? Orm: Very clever. Very clever. Patrick: What were the stages from that first battle that led to your capture? Orm: Well we just reformed, got back to our battalion, and started all over again. We moved into different positions and went to this place called Ruweisat Ridge. That was the last battle I was in. We came under heavy fire again from the Germans, encircled again by their tanks, and the whole battalion was taken prisoner. 800 men were taken prisoner! We were told to advance into them, but what they’d done is they’d spread out and came behind us. How’d they expect infantry to advance on armour? Patrick: So did you think the German tactics were superior to the Commonwealth Forces while you were up against them? Orm: Oh yeah, well they took the whole battalion. We were out-maneuvered Patrick: How did it feel to be told your wars over – “Kaputt” ? Orm: Guttered. Patrick: How did you deal with the grief, the stress? –The grief of being captured, the grief of seeing fellow soldiers being killed beside you? Orm: Well it was just part of the job I think. Just something that had to be done. It all works out really. The discipline you were first taught when you went into camp. It was the mental discipline that carries you though. I definitely think in my own case that you discipline yourself. And if you don’t have the discipline then you just fall to pieces. Patrick: Do you think you’d be able to explain something that you may have experienced about the how the lack of discipline led to a break down? Maybe you saw a solider that wasn’t very disciplined and broke down or couldn’t handle it? Orm: Aw we had them in the army. One particular chap, I won’t mention any names. He was a chap that was always boasting that he could do this, he could do that. Always running someone down, had no time for the officers, no time for discipline. The first day we went into action he broke down. We had to protect him, get him back off the road and they had to take him off the front line. Patrick: How did he break down? Orm: His nerves went. He was always good criticising everyone. He’d done a great job of that. – Criticizing the system. But when the system was put into action he couldn’t handle it! (chuckle). You understand what I’m talking about? You can put it in another way; it’s the loud mouths that criticise everyone, but come off the worse. Patrick: Did you ever see any cases of men sort of giving up? Orm: Yep, some couldn’t handle it. They just sort of broke down and lost their nerves. They had to be helped a lot from there. Life as a POW:Patrick: How well prepared were you for the possibliy of becoming prisoner?Orm: Well we were well prepared for it. We were prepared, we always thought that you could get killed, you could get wounded, but we never thought that we could be taken prisoner of war but that’s what happened to us. We where taken prisoner of war. Patrick: What did you notice of the German morale? Did you notice it was quite high? Orm: Yeah, they gloated. They knew they were holding the upper hand at the time. The smile was taken off their faces later on. Patrick: How was their initial treatment towards you? Orm: Rough, it was rough at the start. We were in make-shift huts in the desert, We were in a big camp at Benghazi. There were no huts or anything. It was just a barb-wire compound until they found ships to take us to Italy. We made makeshift bivis. We had no supplies, just the clothing we stood in. They fed us bare rations. We just sort of tried to keep fit, walked around all day. You couldn’t go very far because you weren’t strong enough at the time. Had to keep fit and keep your mind occupied. They used to make their own cricket balls out of string and footballs out of sacks, (chuckle), we always had something to do to keep their minds off the job. They came around and gave us cards, coloured cards and it depended on the coloured card you got to what ship you were on. Mates were trying to swap round with someone so as they could go with their mates. Two of those ships that went from Benghazi to Italy, got torpedoed in the Meditteranian by our own Navy. A lot of POWs were lost. Patrick: How long was it till the navy figured out they’d made that mistake. Orm: Well I don’t think they did know who was on it. They didn’t know what the Germans and Italians had as cargo. They knew they were foreign ships and they just sunk them. Patrick: While waiting for these ships, were the Germans offering much assistance? Orm: No no no, we were just treated as prisoners or war. They just gave us mega rations, a bit of bread and water. They just had to keep us alive. We got no favours from them. Patrick: How did they treat your wounded? Orm: Well we had a lot of our own medical corps taken prisoner at the same time, -doctors and medical staff. They looked after alot of our wounded. But they never had sufficient supplies. Patrick: They never offered any sort of help? Orm: No, no. Patrick: How was the German treatment in comparison to the Italians? Orm: Oh, the Germans were far superior to the Italians. Patrick: What about the Italian Soldiers treatment towards prisoners. How did that compare? Orm They were inexperienced compared to the Germans. They never had the discipline that the Germans had. Germans were more understanding. And once we got to Italy we got covered by the Geneva Convention – then they had to treat us well or else their own prisoners were treated the same as us. It was a mutual agreement. It was a little bit better once we got to a registered POW camp. When we were sent to the German Prison camps we found what they called the Hitler Youth. We used to be very weary of them, because if we escaped and were caught by them, they showed us no mercy. Patrick: Where were you taken to when you first landed in Italy? Orm: From Taranto to Bari to Udine in Southern Italy. It was only a holding camp, and then they sent us to a camp in Northern Italy that was about 5000 men, Australians, South Africans, Englishmen, New Zealander’s. It was a big camp. Patrick: What were camp conditions like there? Orm: They were average. You did get a hut to sleep in, a straw mattress and a blanket. But it wasn’t till later on that we got a bit of clothing that we sadly needed. That was done through to the Red Cross. Patrick: Did the Italians at all assist with sicknesses that came about through the camp conditions? Orm: Yep.Yeh. Patrick: They were sympathetic towards that? Orm: Yep, well sort of, they did have doctors. Patrick: How did the troops keep their morale up? Orm: You had to make the best of it. We were probably fortunate as a lot of the chaps were out of our own unit and we kept together. Probably bonded us better too, made us stay together, made alot of friends. We just had to make the best of it. –That was the only way to survive. Do the best you could. And put up with the hardships. Patrick: Tell me a little bit about what they fed you? Orm: Feed us? We used to get coffee for breakfast, or something they said was coffee. In some of the camps we were in we did get a portion of a Red Cross parcel -depended on who had arrived, whether we shared it with 5 or 7 others. Might be lucky and get a full one, but not very often. Our ration was bread and one meal a day where we’d get a stew, or a watery soup. Just enough for you to exist on. In Germany you used to get a lot of sauerkraut - cabbage. Patick: What sorts of things did they get you to do in the working parties? Orm: Oh, I worked in all sorts of things, - bricklaying, railway lines, digging irrigation ditches. All those sorts of things. Patrick: Did you ever at any time start talking to any of the guards that were on duty, - like strike up a conversation? Orm: Oh yes, yeah. Patrick: How did that feel to you? Did it sort of break the barrier between enemies? Orm: Tried to, yeah, a lot of the guards were alright. They didn’t want to be there as much as we were trying to get out. Most of the guards were reasonable. The ones that were Hitler’s Special force, the SS, they were the dangerous ones. And then you had the secret police, what’d they call them, the Gestapo. They were pretty hard blokes. Patrick: Did any of the guards openly tell you that they didn’t want to be there? Orm: Yeah! Oh yeah. Patrick: Did you ever come across any of them downing Hitler to you? Orm: No, no, they didn’t do that. Patrick: How did they change towards to end of the war? Orm: They mellowed, they mellowed a lot towards the end of the war. They could see what was going on. Patrick: Do you think they were maybe still behind Hitler? Orm: No, no. I think they saw that they were being led up the wrong path and were fighting a losing battle. That was towards the end. Patrick: At any point did you strike up relationships with the guards regarding trading? Orm: Oh yes, definitely. But it didn’t get you far. Patrick: Were you at any time able to upset the guards in a way that you could bribe them? Orm: Yes, yes. Patrick: Can you account of an occasion when that happened? Orm: They would come round and count everyone in the huts at night time before lights out. And in a hut there’d be about a 100 prisoners I suppose. These guards would come round to make sure we were all there. One of the tricks we used to do was to put a packet of cigars in one the guards pockets and the bloke at the other end of the hut would tell the other guard and of course he’d then get in trouble for trading. Patrick: Can you remember any callous acts from the guards that were really uncalled for? - any real fanatical acts? Orm: Oh yes. There was a prisoner named Jordy, and he had a grudge against the Germans. We were marching home from a job we were on and the Germans had flags hanging out with Swastikas on them. And this guy had a cigarette lighter and went to light fire to one of these flags. The Germans just shot him on the spot. Didn’t ask any questions, which was the wrong thing to do. Although it was the blokes own fault, they shouldn’t have done it really. Patrick: How did the germans punish those men that bucked the system? How did they treat prisoners who got caught trying to escape? Orm: Well, most of the time they put you in solitary confinement which was bread and water for maybe about a fortnight. But I did solitary confinement for three months! Not for escaping though. We had a concert party in a camp and it was a good show. They said they would like to get some photos of it and asked me if I could get a camera. So when I was out in the working party I said to one of the blokes “Can you get me a camera? Do you know anyone who can get one?” He said “You know a camera in Germany is a dangerous weapon.” So he arranged for a woman to get a camera for me, and they took the photos and everything was ok. I took it back to him, and he got the photos developed, smuggled them back into the camp and everyone was quite chuffed about it and said “oh well can you get some more?” So like a mug I said yeah, I’ll try. So this Jaffa and I took them back and said to this guy “can you get some more prints, you know, photos off the wall?” “yep yep” he says. We’re paying him in cigarettes and awwh, the second time we got caught. Whether he gave us away or someone gave us away I’m not certain. As soon as this cobber (good friend) and I who were doing the job, get back inside the camp we got marched away and locked up, court martialed and put in solitary confinement. Patrick: When you say you may have been snitched on, Do you think that another prisoner could have let the gaurds know in order to get special privileges? Orm: Oh, we always had our suspicions, but we could never prove it. Patrick: So you found that a big part of survival depended on the moral encouragement that each prisoner gave one another? Orm: Yes, yeah, Everyone had to work together really. We had to work and stay together. Be no good to have someone there that was on the German side. What they used to do in the camps is they had a hut commander, normally an NCO and he used to go to the trouble of organizing inmates of the hut to give talks at nighttime of what they’d done in their civilian lives. It was very interesting to hear and kept everyone’s sprits going. The camp commander did a great job really. They boosted morale and kept everyone on an even keel. There was a very strong, very strong fellowship in there. There still is. Yes, a very strong bond. Patrick: Did you ever see any guys that were maybe stir crazy and just ran for the wire? Orm: Yes, many times. They used to call them barb-wire happy. A lot of them couldn’t take it. The Germans just fired at them, shot them because there was a wire that you weren’t allowed to pass, they called it a trip wire, and if you put a foot over that you were gone. And a lot of them did. Break down and make a dash for the wire. I think it was just how you were able to pull through, how you were able to discipline yourself. Once you had that, then you knew what you wanted to do - Carry On! You made sure not let them think they were getting the better of you. Patrick: Are there any specific incidents regarding the crossing of the wire that have stayed in your mind? Orm: Hah, yeah. I got caught between it once but I was lucky, just my luck. I got hcaught out. I didn’t break down, I was trying to escape. They had the two sets of wire, a concertina wire and the main line. A cobber (good friend) of mine got out, whether they saw him or they saw me I don’t know but they started shooting and I had to go back. I got back alright, luckily they missed me. Escapes:Patrick: How did you come to the decision that you were going try and escape? What were your thoughts about what you would do if you did get out?Orm: Well a lot of things happened to me but I made up my mind that I was going to be a rebel, that I was going to do what I wasn’t suppose to. I escaped many times and got caught, - and put back into different places. I changed my name with other blokes, but I never made others join, it was just me. I just to had to try and annoy the Germans the best way` I could. Patrick: Can you able to tell me about the first time you escaped? Tell me what lead to you getting over the wire? Orm: It was always on our mind, it was on everyone’s mind to escape but you had to wait until you had the right opportunity. Eventually we got taken out of that big camp 57 and we were put into working camps. They were a little bit better because you were getting more exercise, and your mind was changing because you had something to do, you were occupied. All the time you were there in your own mind, you were scheming to see what you could do. It was quite a while before I decided to have a go. A couple of us did try earlier but we never got very far the first time we tried. As the British troops got closer to driving the German troops out of Italy, they abandoned a lot of camps. That’s where I made my first major escape. Sometimes we got help from the villagers, but they were frightened if they helped that then they’d get caught. But they did give a little bit of help. They told us that if we could get to a town in Northern Italy called Gorizia, on the Yugoslav border, the Yugoslav Partisans, which were pirates, yoobies, - would assist us to get back to the Middle East. So a friend and I got up to this Gorizia, met the Partisans, and they took us up into the hills to their camps. They said they could help us but we had to help them first. So it meant that we had to go on raiding parties with them at night. That wasn’t very nice. They took us back into Italy on these raiding parties. They’d just go up to a house and they’d know there were no men there, they were all on the front lines. They would just knock on the door and the woman would come to answer it, they’d just open up with their machine guns and ransack the house. Then they would make us carry all the spoils back to their camp. Then they’d take us out on raids to blow up trains by putting dynamite in the coal. We had to escape from them because we’d had enough of that. We were there for about a week and escaped when we could. We were captured again by Germans from the Hitler Youth because we were over the border of Yugoslavia, into Austria. We were only out for about 2 or 3 weeks before we were caught again. Patrick: Was it just about as hard to escape from the Yugoslavs as it was from the Italians? Orm: Yeah, you could say we were their prisoners. We then got taken to Spittal in Austria, and that was my first camp in Austria, just over the Yugoslav border. Patrick: Did the conditions of the Prison Camps depreciate once you entered Germany? Orm: Oh yes. They were much stricter and the working parties had to work harder. We used to do everything we could to get out of those working parties. There were all sorts of tricks we used to get up to to try and not work. Patrick: Are you able to explain to me some of these tricks? Orm: One was that they used to rub into your skin, some grease or Vaseline, what ever you could get and wrap your arm up and it would go all soft and bleed. Then we used to tell them it was Desert exma, very contagious, and then they’d stop us going out to work with the other prisoners (Ha ha). Patrick: What sort of work did you do? Orm: Oh, on farms, digging potatoes, on the railway, changing the lines, putting in new lines. Could be little building projects, manual labour mostly but it was through these working parties that some of us could escape. Patrick: Are you able to recall another memorable escape or escape attempt? Orm: Oh, when we were sentenced to our court marshal, a cobber of mine and I were told they were taking us to Plouwan they took us from the Stalag, we went in up to Poland. There were five of us and a Polish bloke. The Polish bloke could speak a little bit of English, he said when we get across the border into Poland you follow me, “get out, don’t stay”. So when we got to Poland and the train pulled up we found that instead of having one card each, we needed 2 cards each to get passed the check point. The Pole walked free. I suppose that was what he was going to do all along. All the guards got stuck into us and he walked free. So anyhow we didn’t get very far into Poland and the Germans were chased back through Poland by the Russians, and they had to take us all the way back from where we’d come from and we got to a place called Posen. We had nothing to eat for about 5 days and so this Scotch friend of mine said well this is no good we’ll escape from this train and find something to eat. So we escaped from our guard, went off the railway station, went into the street and gave ourselves up to a bloomin policeman. He said “you POW” and so he arrested us and we spent the night in the cell on the concrete floor but he gave us a feed and then handed us over to our guard the next morning. So we got something to eat. Patrick: What was the reception like the next morning from those guards? Orm: Good, Oh they were happy because they’d made an arrest. Patrick: What about the guards that took you back at camp? Orm: Oh they gave us hell - they took our bootlaces and belts off us so we couldn’t get away again. Patrick: How many times did you escape over the years? Orm: Oh, I’m not sure, I lost count. Patrick: Did you get any recognition of that when you were sent back to camp? Orm: Nah, nobody knows anything about it. See that’s the worst thing about it, I wasn’t married then, I was engaged, but well she’s my wife now, my mother and father and family, they didn’t know where I was. I could write letters but they didn’t know where I was. They knew I was a POW but it took them 12 months to find out. They didn’t know what was going on. They use to write, but then it’d have to be censored, I couldn’t tell her how I was doing. Patrick: Back to that time when you were in the desert, how strong were you, what was your physical strength like? Did you fear any of the guards? Orm: Never. I never feared them at all. I was around about 11 ½ stone when I went into the army when I was taken prisoner. And when I got to England I was 6 stone. Patrick: Can you remember any noticeable differences between the way the Italians and Germans ran their camps? Orm: Yeah, the Germans were always stricter. But if you could get out on a working party you had more chance of getting away. There were plenty of opportunities I suppose if you like to take the risk. We took plenty of risks. Patrick: Are you able to describe what you considered to be the biggest risk you took? Orm: Aw, that was when we did get away, right towards the end of the war, they evacuated Stalag XVIIIA which we were in and made all the troops march. All the disciplinarians - the ones that had played up and escaped were taken by train. I was one of them, I didn’t have to march. They took all our shoelaces, belts, and braces so as we couldn’t escape, so we couldn’t run anywhere and landed us in this camp that was down by the Yugoslav and Austrian borders. The place was called Markt Pona. It was there that I met up with an old Cobber of mine who I’d tried several times to escape with. We had spent time in Colditz together after getting caught during an escape attempt. No one had ever escaped from there. And until they sorted us out and found out what camp we’d come from and they could send us back where we had escaped from. Once they sorted things out, they sent us back. They said to us at Colditz “If you have one more go, you’re dead.” We didn’t pay to much attention to that sort of talk. Anyway, we heard the news that the Americans had taken a town in Austria called Innsbruck. They had a wireless in the camp that let us follow the Allied broadcasts. We had a fair idea where Innsbruck was so “he said why don’t we get out and have a go at getting there”, so we did. We got out of the camp alright and met a woman who we assumed worked at the railway station. Incidentally this Cobber of mine had learnt German at school and could talk perfect German. He asked her if there were any trains that went through the Station we were at to Innsbruck. She told us one went through at 2 o’clock in the morning. So we had to hide up until then. We had no watches so one of us had to keep going back and having a look at the clock on the railway station until 2 o’clock. When we guessed it was the right time my cobber whispered “Here’s one coming” so we jumped on it. We never made a sound and no-one on the train was talking. We got on the train and at day light it stopped. Then my mate heard these Germans talking and he said “were in trouble here, it’s a German troop train!” He said to get in the toilet, so we did. Then we heard them giving the orders for all the troops to get out and form up on the right hand side of the train and they were going to march. And he said to me “When I say go - Go” and we got out on the left side and went for our life up into the bush. We got away! We were up in the forest for about 7 days. We could see both sides fighting but we couldn’t see who was who and were frightened to come back down. Patrick: Was it quite a fierce battle that was going on? Orm: Yeah, tanks and what have you. Patrick: Even the Germans? They had tanks at this late stage? Orm: Yep, yep. They still had some. It was aeroplanes, it was everything. We stayed in the forest for a few days then we took our chances and went down. We were lucky they were the Yanks. Then they took us and gave us a feed. They wouldn’t accept us at first, they didn’t know whether we where spies or what. Because we told them where we came from such n such place and they didn’t know where it was. Anyhow they took us to Munich where they were helping those prisoners of war that had been liberated by the Americans and flying them back to England. So we went up to the joker in charge and told him who we were and he said oh no that camp hasn’t been relieved yet. And we said yes, we know it hasn’t but that’s where we’ve come from. He wouldn’t accept us. So we said alright, and were just walking across the airfield at Munich, met a Yank, and got talking to him. I said to him as a joke “Where are you going!” He said to Brussels, and we said “well what about a ride?” and said oh no I cant give you a ride, see the boss, see the captain, so we went to him and he said “Oh well, if you want to take the risk you can come”. So he took us. We got a ride in a plane to Brussels, he arranged for us to fly to England the next morning. Patrick: Are you able to tell me about the time the Americans offered for you to go down and confront the German prisoners that they had captured and what that lead to? Orm: That was in Innsbruck. When they took us prisoner they stripped us of everything we had, rings, watches and they took the lot. The Americans said they had some German POWs down there and asked if we wanted to do what they had done to us? So we said oh yeah, so we went down and decided that No we didn’t. We just left them to it. Anyhow, I think it was many years later, when I was married, had come back to New Zealand, and shifted from Wellington to Palmerston North and rejoined the fire brigade. I’m not sure how many years it was after the war, must have been a good ten years. I had a Cobber that had a panel beating shop and spray painting business. And I’d learnt a bit of spray painting with cars, and I used to go on my day off from the fire brigade and give him a hand spray painting. One day he said to me, “you’re going to be a bit embarrassed” he said at morning tea-time. He said I’ve got a German here, he said he was a prisoner of war. And I said “oh well that won’t embarrass me.” So anyhow I went and I said to this chap “where were you taken POW and he said Innsbruck and I said “Oh, I was at Innsbruck and saw some German POWs behind a makeshift pen with barbed wire” and he said “Yea, two of you, one was a blond bloke.” I said “that’s right, that was my mate.” He remembered us, he certainly remembered the occasion. So he said to me to come and have a beer with him. So we went to his house. I talked his wife and she wasn’t very happy. She just had a grudge against British, New Zealanders, because she had lost her father, her two brothers and an Uncle in the war. She just had a thing about it. He never stopped here, he went on to Aussie. Patrick: So what sort of reception did he give you? Orm: Oh he was alright, he thought it was a great joke. (Ha ha) Patrick: And how about you? Orm: Oh didn’t worry me, it was quite an experience really. When it’s all boiled down, - we fought for 5 years, we fought a an enemy that had to be stopped, we won the war, we beat the Axis, but we still haven’t won the peace. There’s still wars. We fought that war to say it was the war to end all wars but what have we been doing? We’ve been fighting wars ever since all around the world. So we’ve achieved nothing! |